Theatre Songs that Shaped Modern Malayali

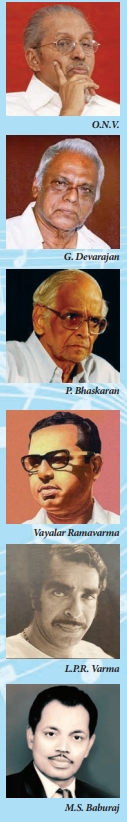

There are numerous luminaries who have been at the forefront of creating a renaissance in Malayalam music. This illustrious group comprises poets, lyricists, music directors, and singers, forming a vast array of talent. Among the foremost and highly regarded lyricists is P. Bhaskaran Master. When his songs were published in a collection titled “Naazhiyurippal” in 1992, the introduction contained a particularly notable observation. “During that era, the Malayalam theatre scene largely mirrored Tamil dramas, resplendent with keertanas, the rhythmic chime of the harmonium, and intricate sapta swara exercises. These were often plays devoid of real-life touchstones. Traditional art forms like Kathakali songs were not integral to the music of the masses. Folk songs primarily remained the cultural treasure of a marginalized section, resonating through the paddy fields and coconut groves. In essence, Malayalis lacked simple melodies to sing or spirited anthems for nationalists and revolutionaries to chant with vigor. It was against this backdrop that I was compelled to pen songs, addressing a historical need of the era.” Before the 1940s, apart from the Carnatic music’s Keerthanas and elaborate Ragas, there were primarily folk songs, anonymous compositions, and rustic tunes.

There are numerous luminaries who have been at the forefront of creating a renaissance in Malayalam music. This illustrious group comprises poets, lyricists, music directors, and singers, forming a vast array of talent. Among the foremost and highly regarded lyricists is P. Bhaskaran Master. When his songs were published in a collection titled “Naazhiyurippal” in 1992, the introduction contained a particularly notable observation. “During that era, the Malayalam theatre scene largely mirrored Tamil dramas, resplendent with keertanas, the rhythmic chime of the harmonium, and intricate sapta swara exercises. These were often plays devoid of real-life touchstones. Traditional art forms like Kathakali songs were not integral to the music of the masses. Folk songs primarily remained the cultural treasure of a marginalized section, resonating through the paddy fields and coconut groves. In essence, Malayalis lacked simple melodies to sing or spirited anthems for nationalists and revolutionaries to chant with vigor. It was against this backdrop that I was compelled to pen songs, addressing a historical need of the era.” Before the 1940s, apart from the Carnatic music’s Keerthanas and elaborate Ragas, there were primarily folk songs, anonymous compositions, and rustic tunes.

The transformation began in the 1920s and 1930s as the national movement and the struggle for independence gained momentum. Across India, a society fragmented into diverse religious, caste, and linguistic communities was being inspired towards a consciousness of national independence through luminous tales of struggle and songs in various languages. Songs like Iqbal’s “Sāre Jahān se Achchā, Hindustān Hamārā,” Bharatiyar’s “Pārkullē Nalla Nādu, Engal Bhārata Nādu,” Vallathol’s “Pōrā Pōrā Nāļil Nāļil Dūradūramuyarattē,” Bodheswaran’s “Jaya Jaya Kōmala Kērala Dharani,” Amsi Narayana Pillai’s “Varika Varika Sahajarē, Sahana Samara Samayamāy,” and Vidwan P. Kelu Nair’s “Smarippin Bhāratīyarē, Namippin Mātrbhūmiye” began to emerge, albeit sparsely, with new rhythms, melodies, and languages. It is on this path that, in the early 1940s, Bhaskaran Master’s Unification of Kerala song, “Padam Padam Uracchu Nām Pādippadippōvuka, Pāril Aikya Kēralattin Kāhalam Mulakkuvān,” was born.

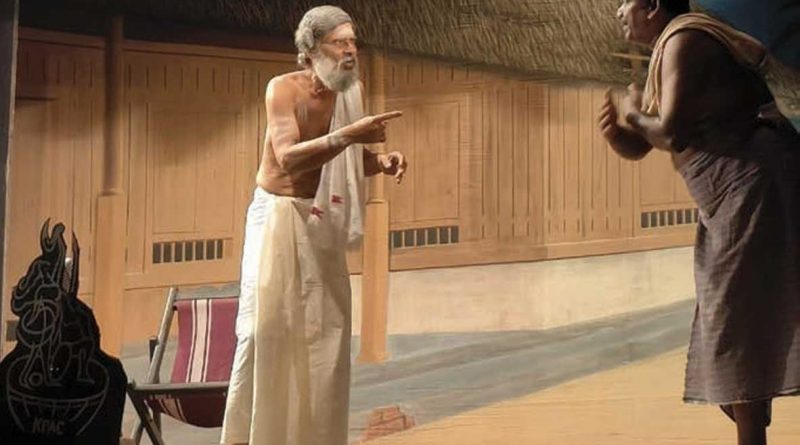

Amidst the mesmerizing renditions of semi-classical songs in Tamil-Malayalam musical dramas, the era was eagerly awaiting the birth of a popular music genre that embodied simplicity in both lyrics and melody, reflecting the progressive aspirations of the people. In 1952, following in the footsteps of IPTA, the Kerala People’s Arts Club (KPAC) was formed. The initial theatrical venture of KPAC, born under the leadership of K. Janardhanakurup, Rajagopalan Nair, and Sreenarayanapillai at the CPI conference in Trivandrum, was “Ente Makananu Sari” (“My Son is Right”). The songs for this play were penned by Punalur Balan. These songs, crafted in the tune of folk music, did not have a designated music director. The next play that made history was “Ningal Enne Communistakki” (“You Made Me a Communist”). In reality, it features a song that marks the beginning of all subsequent songs we hear. This was not originally written for the play. It was a poem titled “Irulil Ninnoru Gaanam” (“A Song from the Darkness”) penned in 1948 by O.N.V. Kurup, who was a student at S.N. College, Kollam. It was only four years later that this poem was printed in the Communist Party’s newspaper, edited by Vaikom Chandrasekharan Nair. Devarajan composed music for it, leading to the creation of the famous song “Ponnarival Ambiliyil Kanneriyunnoole.” This song was later incorporated into the play “Ningal Enne Communistakki.” However, this song holds a historical mission. “Ponnarival” was the pioneering model for all subsequent drama and film songs we have heard. O.N.V. Kurup’s lyrics, set to music by Devarajan and performed by K.S. George, KPAC Sulochana, and their troupe, comprised 26 songs in ‘Ningal Enne Communistakki.’ Starting with the introductory song ‘Deepangal Mangi Koorirul Thinghi,’ many of these songs remain deeply imprinted in the hearts of the people.

Amidst the mesmerizing renditions of semi-classical songs in Tamil-Malayalam musical dramas, the era was eagerly awaiting the birth of a popular music genre that embodied simplicity in both lyrics and melody, reflecting the progressive aspirations of the people. In 1952, following in the footsteps of IPTA, the Kerala People’s Arts Club (KPAC) was formed. The initial theatrical venture of KPAC, born under the leadership of K. Janardhanakurup, Rajagopalan Nair, and Sreenarayanapillai at the CPI conference in Trivandrum, was “Ente Makananu Sari” (“My Son is Right”). The songs for this play were penned by Punalur Balan. These songs, crafted in the tune of folk music, did not have a designated music director. The next play that made history was “Ningal Enne Communistakki” (“You Made Me a Communist”). In reality, it features a song that marks the beginning of all subsequent songs we hear. This was not originally written for the play. It was a poem titled “Irulil Ninnoru Gaanam” (“A Song from the Darkness”) penned in 1948 by O.N.V. Kurup, who was a student at S.N. College, Kollam. It was only four years later that this poem was printed in the Communist Party’s newspaper, edited by Vaikom Chandrasekharan Nair. Devarajan composed music for it, leading to the creation of the famous song “Ponnarival Ambiliyil Kanneriyunnoole.” This song was later incorporated into the play “Ningal Enne Communistakki.” However, this song holds a historical mission. “Ponnarival” was the pioneering model for all subsequent drama and film songs we have heard. O.N.V. Kurup’s lyrics, set to music by Devarajan and performed by K.S. George, KPAC Sulochana, and their troupe, comprised 26 songs in ‘Ningal Enne Communistakki.’ Starting with the introductory song ‘Deepangal Mangi Koorirul Thinghi,’ many of these songs remain deeply imprinted in the hearts of the people.

Songs like ‘Neelakkuruvi Neelakkuruvi Neeyoru Kaaryam Chollumo,’ ‘Moolippaattumaai Thambraan Varumbam Choolathangane Nilledi Penne,’ ‘Innale Naattoru Njaarugalellaam Punnelkkathirinte Polkudam Choodi,’ ‘Ponnarivaal Ambiliyil,’ and ‘Vellarankunnile Ponnmulam Kaattile’ continue to resonate with the public even after many years. The general characteristics of these songs lie in their raw essence of life and connections, both in lyrics and music. In the early 1950s, the theatrical song genre thrived, infusing local Malayalam, rustic expressions, and the familiar tunes of folk songs into the ears of people who had been accustomed to hearing the complex Sanskrit words and elaborate Carnatic Ragas in the mythological musical dramas filled with kings, queens, gods, and goddesses. The path paved by the songs in KPAC’s “Ningal Enne Communistakki” continued to be travelled by our later film songs. The song “Ponnarival Ambiliyil,” which initiated this, is simultaneously a love song and a revolutionary anthem. It is a flowering tree where love and revolution blossom on each branch, as epitomized in the lines, “Paadukayaanen Karal, Poraadumen Karangal” (“My heart sings, my hands fight”).

Even in love, there is a childlike innocence and adolescent mischief not only in the lyrics but also in the music. In the radiant spring of popular art in the 1950s, cinema and theater both witnessed the creation of exceptional songs. The inspiration for this came not from elsewhere but from KPAC and “Ningal Enne Communistakki.” Plays like “Mudiyanaya Puthran,” “Sarvekkallu,” “Puthiyaakasham Puthiya Bhoomi,” “Ashwamedham,” and “Sharashayya” from KPAC were showers of the flowering tree of songs. The Kalidasa Kalakendram, established in Kollam in 1962, can be seen as both a break from and a continuation of KPAC. Through plays like “Doctor” and “Janani Janmabhoomi,” O.N.V. Kurup and Devarajan, the founding fathers of our theatrical song genre, initiated the deluge of Kalidasa songs. Other theater groups like Kerala Theatres in Kottayam, known for plays like “Kathiru Kaanaakkili” and “Visharikku Kaatu Venda,” and Pratibha Arts Club in Ernakulam, with plays like “Mooladhanam” and “Kaakkapponnu,” also provided Malayalam audiences with excellent songs through their dramas. Alongside this, Cherukad’s play “Nammal Onnu” also deserves mention. Premiered as early as 1948, the lyrics were crafted by Ponkunnam Damodaran and Vayalar.

The music was composed by P.K. Sivadhas and Baburaj. Songs that captivated the hearts of millions, such as “Iru Nazhi Manninnai Urukunna Karshakan,” “Pachappanantatthe,” and “Punnaarappoomuththe,” remain unforgettable. In a TV interview, K. Raghavan Master mentioned that the primary influence on the songs he composed for the 1954 Ramu Kariat-P. Bhaskaran film “Neelakkuyil” was indeed the Malayalam theatrical song genre. Luminaries like O.N.V. Kurup, Devarajan, Vayalar, L.P.R. Varma, P. Bhaskaran, Baburaj, and Ponkunnam Damodaran have all significantly bolstered this popular musical tradition in both theatre and cinema.