From Melody to Modernity

Not that anything particular happened in 2000, but many changes occurred at the dawn of the new century, and so did films. What has happened to the songs in the films is consequential to what happened to cinema. Along with the easy access to versatile technologies, the themes and treatment of films underwent a paradigm shift. Issues and concerns that were once considered unsuitable and too daring made an easy entry into films. The younger filmgoers, free from the usual preconceived ideas and judgements, approached the new films with a fresh mind and an appetite for novelty and boldness. The distinction between award films and popular films slowly got erased. Generation X, accustomed to fast actions and decisions, thanks to digital technology, demanded a fast pace of narration that broke with the conventional scripting style where everything is explained. The pace of storytelling changed. Themes changed. Conventional sentiments were interrogated, leading to what is loosely called ‘Newgen’ films.

Not that anything particular happened in 2000, but many changes occurred at the dawn of the new century, and so did films. What has happened to the songs in the films is consequential to what happened to cinema. Along with the easy access to versatile technologies, the themes and treatment of films underwent a paradigm shift. Issues and concerns that were once considered unsuitable and too daring made an easy entry into films. The younger filmgoers, free from the usual preconceived ideas and judgements, approached the new films with a fresh mind and an appetite for novelty and boldness. The distinction between award films and popular films slowly got erased. Generation X, accustomed to fast actions and decisions, thanks to digital technology, demanded a fast pace of narration that broke with the conventional scripting style where everything is explained. The pace of storytelling changed. Themes changed. Conventional sentiments were interrogated, leading to what is loosely called ‘Newgen’ films.

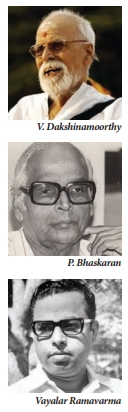

This is indeed a misnomer; it merely refers to contemporary cinema. There cannot be an ‘Oldgen cinema’. Although these changes are felt throughout the film world, Malayalam cinema is a few steps ahead of other languages in its thematic audacity and narrative boldness. Songs in Malayalam films have, in the past, played a key role in their box office success. The popularity of the songs lured the audience to watch the films. Good songs commanded a place of primacy in films until the early years of this century. Their importance and quality however began to decline since the late 80s, though memorable songs continued to appear. Undoubtedly, the golden era of Malayalam film songs spans the three decades from 1960 to 1980. Legendary composers like G. Devarajan, M.S. Baburaj, and V. Dakshinamoorthy created an enchanting period up to the mid-seventies.

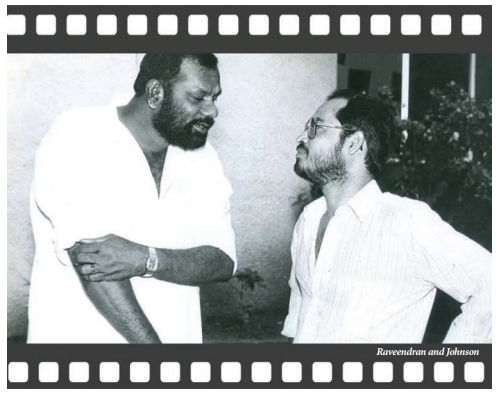

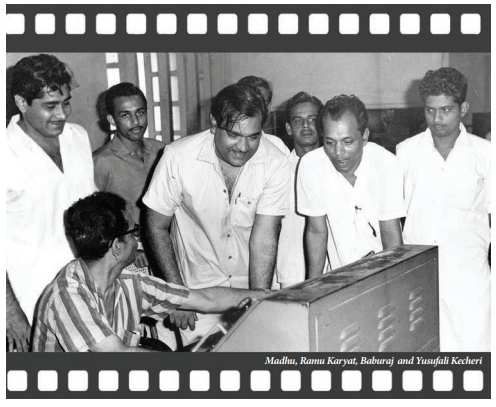

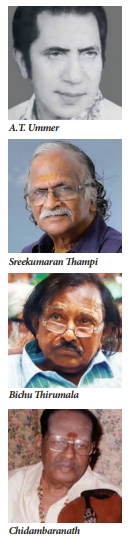

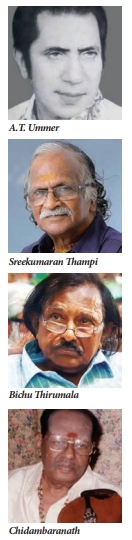

Poets-turned-lyricists like P. Bhaskaran, Vayalar Ramavarma, and O.N.V. Kurup enriched Malayalam films with everlasting lyrics. Many songs, by virtue of their lyrical and musical greatness, had a life beyond the context of the films. Alongside these great lyricists and composers, we must recognise the equally powerful presence of lyricists like Sreekumaran Thampi, Yusuf Ali Kechery and Bichu Thirumala. Sreekumaran Thampi entered the industry in the 60s and went on to pen several thousand songs remembered for their directness and simplicity. Composers M.K. Arjunan, A.T. Ummer, Chidambaranath, and later Johnson and Raveendran, made Malayalam film songs varied and rich. The songs featured in films until 1990 were mostly romantic, celebrating the bonding between the hero and the heroine. The lyrics generally dwelt on the beauty of the girl, who in return would offer herself to the hero.

Poets-turned-lyricists like P. Bhaskaran, Vayalar Ramavarma, and O.N.V. Kurup enriched Malayalam films with everlasting lyrics. Many songs, by virtue of their lyrical and musical greatness, had a life beyond the context of the films. Alongside these great lyricists and composers, we must recognise the equally powerful presence of lyricists like Sreekumaran Thampi, Yusuf Ali Kechery and Bichu Thirumala. Sreekumaran Thampi entered the industry in the 60s and went on to pen several thousand songs remembered for their directness and simplicity. Composers M.K. Arjunan, A.T. Ummer, Chidambaranath, and later Johnson and Raveendran, made Malayalam film songs varied and rich. The songs featured in films until 1990 were mostly romantic, celebrating the bonding between the hero and the heroine. The lyrics generally dwelt on the beauty of the girl, who in return would offer herself to the hero.

This gender stereotype, though out of sync with modern-day equations, was the most celebrated theme in film songs until the 90s. Other occasions for songs were sentimentally rich sequences of parting, death, and other misfortunes. These situations allowed writers some leverage to philosophise and touch certain emotional chords. These moments have given us several everlasting songs like ‘Mangalam Nerunnu Njaan,’ ‘Sanyasini Nin Punyasramathil,’ and ‘Sukhamoru Bindu Dukhamoru Bindu.’ All these usual situations have undergone a major shift in their emotional settings in films post-2000. Of course, characters still fall in love and part ways. Still misfortunes befall characters. But such situations do not always warrant a song as such human situations are now approached differently. It is now almost impossible to expect a love song like ‘Anupame Azhake’ or ‘Sahyadri Sanukkal Enikku Nalkiya Soundarya Devatha Nee.’

the 90s. Other occasions for songs were sentimentally rich sequences of parting, death, and other misfortunes. These situations allowed writers some leverage to philosophise and touch certain emotional chords. These moments have given us several everlasting songs like ‘Mangalam Nerunnu Njaan,’ ‘Sanyasini Nin Punyasramathil,’ and ‘Sukhamoru Bindu Dukhamoru Bindu.’ All these usual situations have undergone a major shift in their emotional settings in films post-2000. Of course, characters still fall in love and part ways. Still misfortunes befall characters. But such situations do not always warrant a song as such human situations are now approached differently. It is now almost impossible to expect a love song like ‘Anupame Azhake’ or ‘Sahyadri Sanukkal Enikku Nalkiya Soundarya Devatha Nee.’

The tenor of the relationship between young men and women has mutated into a highly informal and playful engagement with each other. The songs have to convey that kind of casualness. Idealization has no place today particularly in love relationship. Naturally, a new lyrical style and a new musical beat and lilt have become necessary. The traditional style of a writer creating the lyrics and then the music director setting them to tune could not do justice to the requirements of the new songs. Thus, the practice of a tune being born ahead of the lyrics became the order of the day. Although this had some justification, it slowly undermined the primacy of the lyrics and the importance of the lyricist. The lyricist’s contribution has now become secondary as the tune, with its westernised orchestration, began to steal the show. As a result, hundreds of songs were created that were rich in musical score but poor in literary value.

The tenor of the relationship between young men and women has mutated into a highly informal and playful engagement with each other. The songs have to convey that kind of casualness. Idealization has no place today particularly in love relationship. Naturally, a new lyrical style and a new musical beat and lilt have become necessary. The traditional style of a writer creating the lyrics and then the music director setting them to tune could not do justice to the requirements of the new songs. Thus, the practice of a tune being born ahead of the lyrics became the order of the day. Although this had some justification, it slowly undermined the primacy of the lyrics and the importance of the lyricist. The lyricist’s contribution has now become secondary as the tune, with its westernised orchestration, began to steal the show. As a result, hundreds of songs were created that were rich in musical score but poor in literary value.

The recall value of such songs is limited as they do not enshrine any worthwhile ideas. The devaluation of the literary quality of the songs has been the most significant cause of their poor shelf life. The widespread craze for English medium education has also catalysed the devaluation of lyrics in Malayalam songs. Many graduates and professionally qualified young people can go through their entire education without being able to read or write Malayalam. For them, anything beyond casual conversation is ‘highbrow literature’. Consequently, filmmakers often insist on ‘simple lyrics’, a euphemism for lines devoid of literary merit. This trend, coupled with anglicised pronunciation and Western-style orchestration, has given rise to a new type of songs in Malayalam, now hailed as trendy and youthful. Whether this is the only possible style or if a better, more acceptable style is on the anvil remains to be seen. Until then, we are destined to endure the cacophony of today’s Malayalam film songs.