Reflections on Malabar’s Folk Music

Extensive studies and scholarly work have been conducted on Kerala’s folk arts and culture, with the University of Calicut even hosting a dedicated folklore department. Numerous academic and non-academic studies and books have emerged in this field. Many non-academic scholars, who may not possess formal degrees or PhDs, have diligently identified and preserved traditional songs, contributing significantly to the understanding of these art forms. These scholars have focused on the collection and study of folk songs. However, research specifically targeting the musical and rhythmic aspects of these songs remains relatively underexplored. There seems to be an opportunity for music scholars and students to deepen their awareness of the cultural value and extensive influence of folk music. This presents a promising area for further academic inquiry and appreciation within the broader scope of Carnatic music and traditional art forms. In the study of Carnatic music, traditional folk music has not been prominently featured. While some exceptions may exist, they are not widely recognized. Early poets did not incorporate certain songs, and similarly, classical musicians have largely excluded folk music from their repertoire. Even compositions based on specific ragas were often dismissed as simplistic and not integrated into mainstream Carnatic music. This exclusion highlights a need for comprehensive study and discussion on the topic. In contrast, North Indian classical music has seen prominent vocalists incorporating folk music into their performances, using it to innovate and create new styles.

Extensive studies and scholarly work have been conducted on Kerala’s folk arts and culture, with the University of Calicut even hosting a dedicated folklore department. Numerous academic and non-academic studies and books have emerged in this field. Many non-academic scholars, who may not possess formal degrees or PhDs, have diligently identified and preserved traditional songs, contributing significantly to the understanding of these art forms. These scholars have focused on the collection and study of folk songs. However, research specifically targeting the musical and rhythmic aspects of these songs remains relatively underexplored. There seems to be an opportunity for music scholars and students to deepen their awareness of the cultural value and extensive influence of folk music. This presents a promising area for further academic inquiry and appreciation within the broader scope of Carnatic music and traditional art forms. In the study of Carnatic music, traditional folk music has not been prominently featured. While some exceptions may exist, they are not widely recognized. Early poets did not incorporate certain songs, and similarly, classical musicians have largely excluded folk music from their repertoire. Even compositions based on specific ragas were often dismissed as simplistic and not integrated into mainstream Carnatic music. This exclusion highlights a need for comprehensive study and discussion on the topic. In contrast, North Indian classical music has seen prominent vocalists incorporating folk music into their performances, using it to innovate and create new styles.

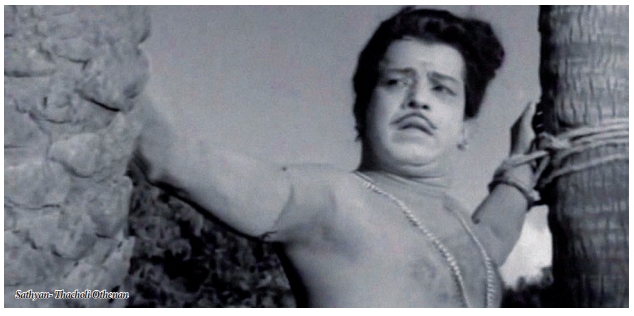

However, in South Indian classical music, folk music has generally been subject to significant restrictions and has not been widely embraced within the classical tradition. When discussing North Kerala, it is essential to explore its folk arts and the musical elements inherent in them. There are numerous cultural and ritualistic aspects from this region that warrant thorough study. One of the prominent features of North Kerala’s musical heritage is the genre known as “Vadakkan Pattu” or Northern Ballads. Notable collectors of these ballads include M.C. Appunni Nambiar and T.H. Kunjiraman Nambiar. Scholarly research and discussions on the linguistic, literary, and narrative aspects of these songs have been conducted for many years. The first film to feature a Vadakkan Pattu was “Unniyarcha,” released in 1961, with music composed by K. Raghavan Master. This film brought the musical style into the mainstream. Following this, the 1964 film “Thacholi Othenan” featured music composed by Baburaj. Both composers successfully extracted the essence of the musical elements embedded in Vadakkan Pattu, using it to create new musical compositions. The tunes commonly sung today as Vadakkan Pattu are a result of their efforts to redefine the musical identity of this genre. Raghavan Master and Baburaj discovered the potential to develop a new musical tradition in Malayalam based on these original tunes.

Kerala, it is essential to explore its folk arts and the musical elements inherent in them. There are numerous cultural and ritualistic aspects from this region that warrant thorough study. One of the prominent features of North Kerala’s musical heritage is the genre known as “Vadakkan Pattu” or Northern Ballads. Notable collectors of these ballads include M.C. Appunni Nambiar and T.H. Kunjiraman Nambiar. Scholarly research and discussions on the linguistic, literary, and narrative aspects of these songs have been conducted for many years. The first film to feature a Vadakkan Pattu was “Unniyarcha,” released in 1961, with music composed by K. Raghavan Master. This film brought the musical style into the mainstream. Following this, the 1964 film “Thacholi Othenan” featured music composed by Baburaj. Both composers successfully extracted the essence of the musical elements embedded in Vadakkan Pattu, using it to create new musical compositions. The tunes commonly sung today as Vadakkan Pattu are a result of their efforts to redefine the musical identity of this genre. Raghavan Master and Baburaj discovered the potential to develop a new musical tradition in Malayalam based on these original tunes.

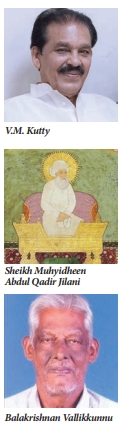

This endeavor was not a formal research project but a creative exploration of the genre’s musical possibilities. Each song within the Vadakkan Pattu repertoire has been individually studied. While the literary world has explored figures like Unniyarcha, Thacholi Othenan, Kunhithalu, Poomathai Ponnamma, and Mathilerikkanni, scholars have not delved into the musical and lyrical aspects of these ballads. Currently, groups performing under the banner of “Nadan Pattu Gana Sangham” have popularized these folk songs by leveraging their inherent rhythmic structure, garnering widespread appeal. Another significant contribution from the Malabar region within the folk song tradition is the Mappila Pattu. As the name suggests, these songs originated from the Muslim community in Malabar and were initially tied to their religious practices. Over time, Mappila Pattu evolved to encompass a broader range of subjects. In Malabar, the term “Mappila” specifically refers to Muslims, while in southern Kerala, it can also denote Christians. This musical tradition is distinctly associated with North Kerala, or more precisely, the extreme northern region of Kerala. Mappila Pattu specifically refers to the songs of the Malabar Muslims. When discussing the musical aspects of Mappila Pattu, it is often simplistically linked to Arabian or Hindustani music. However, it is crucial to examine whether these are indeed its foundational elements. Noted Mappila Pattu singer and author V. M. Kutty has asserted that the true source of this tradition is Kerala’s indigenous folk songs. This perspective invites a deeper exploration of its musical roots, challenging the conventional associations and recognizing its local heritage. Folk songs, traditionally passed down orally, are generally referred to as “Nadan Pattu.” Over time, even written songs have integrated into this tradition, becoming well-established. When discussing Mappila Pattu, the most prominent poet is Mahakavi Moyinkutti Vaidyar, who enriched this poetic genre significantly.

Many poets followed, further enriching the tradition. In other folk song genres like Vadakkan Pattu and Pulluvan Pattu, the authors of the songs are unknown, as these were orally transmitted through generations and only later documented. However, Mappila Pattu stands apart. The earliest known Mappila Pattu, “Muhyidheen Mala,” has a known author. We now know that this poetic work, praising the Sufi saint Sheikh Muhyidheen Abdul Qadir Jilani, was written by Kadi Muhammed Ibn Abdul Aziz. This distinct characteristic of Mappila Pattu has led to arguments that it does not belong to the category of folk songs. Renowned scholar Balakrishnan Vallikkunnu, who has extensively studied Mappila art and literature, has remarked: “In a technical sense, Mappila Pattukal are neither folk songs nor traditional folk songs. They cannot be categorized as social compositions or works aimed at social collectiveness in terms of their creation or reception. The inherent spontaneity and dynamism of folk traditions are rare in these songs. It is not plausible to consider their composition as either meticulously crafted or loosely structured to the extent that the author or reciter can make additions or omissions according to the context of the same social setting. Even though a social limitation can be observed, it is inconsistent to consider them products of a homogeneous social tradition. Hence, categorizing Mappila Pattukal as Nadan Pattu is not an appropriate approach.” Mappila Pattu has evolved and refined itself over time, assimilating various influences from other traditions. It has transcended its local origins, embracing a wide range of human emotions and themes. From nature, love, and sensuality to revolution and freedom, Mappila Pattu addresses an extensive array of subjects, possibly more than any other song tradition.

Many poets followed, further enriching the tradition. In other folk song genres like Vadakkan Pattu and Pulluvan Pattu, the authors of the songs are unknown, as these were orally transmitted through generations and only later documented. However, Mappila Pattu stands apart. The earliest known Mappila Pattu, “Muhyidheen Mala,” has a known author. We now know that this poetic work, praising the Sufi saint Sheikh Muhyidheen Abdul Qadir Jilani, was written by Kadi Muhammed Ibn Abdul Aziz. This distinct characteristic of Mappila Pattu has led to arguments that it does not belong to the category of folk songs. Renowned scholar Balakrishnan Vallikkunnu, who has extensively studied Mappila art and literature, has remarked: “In a technical sense, Mappila Pattukal are neither folk songs nor traditional folk songs. They cannot be categorized as social compositions or works aimed at social collectiveness in terms of their creation or reception. The inherent spontaneity and dynamism of folk traditions are rare in these songs. It is not plausible to consider their composition as either meticulously crafted or loosely structured to the extent that the author or reciter can make additions or omissions according to the context of the same social setting. Even though a social limitation can be observed, it is inconsistent to consider them products of a homogeneous social tradition. Hence, categorizing Mappila Pattukal as Nadan Pattu is not an appropriate approach.” Mappila Pattu has evolved and refined itself over time, assimilating various influences from other traditions. It has transcended its local origins, embracing a wide range of human emotions and themes. From nature, love, and sensuality to revolution and freedom, Mappila Pattu addresses an extensive array of subjects, possibly more than any other song tradition.

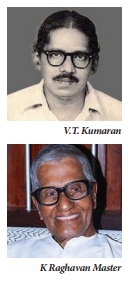

It encompasses all aspects of human experience and has significantly contributed to mainstream light music in Malayalam, enhancing it with its rich heritage. Composers like K. Raghavan Master and Baburaj have enriched Malayalam’s light music by drawing from this art form. The rhythmic structures of Mappila Pattu’s melodies warrant detailed study. This genre is expansive, including Kolkali, Duff Muttu, wedding songs, lullabies, and war songs. Despite this diversity, there appears to be insufficient scholarly focus on its musical and rhythmic aspects. The instruments used, their rhythmic applications, and comparisons with instruments from other cultures deserve attention. The acoustic variations can indeed be recreated using electronic devices, yet we often overlook analyzing the original forms of these sounds. There is a lack of exploration into how our ancestors developed these musical traditions, which could reveal the depth and breadth of this culture’s roots. Examining the construction and history of a single instrument could provide profound insights into our current position and its evolution. This exploration could lead us towards understanding the multicultural exchanges and the rich diversity within our cultural heritage. Theyyam and Thira are ritualistic art forms from Malabar, particularly from the districts of Kannur, Kasaragod, and Kozhikode in North Kerala. Although these art forms combine dance and elaborate costumes, the “Thottam Pattu” (songs) used in Theyyam deserve serious attention from classical musicians. These songs often contain the primitive applications and original forms of the ragas that have been refined in our classical music. Studying the vocal renditions in Theyyam can reveal these early musical expressions, offering valuable insights into the origins and evolution of our musical traditions.

K. Raghavan Master and Baburaj have enriched Malayalam’s light music by drawing from this art form. The rhythmic structures of Mappila Pattu’s melodies warrant detailed study. This genre is expansive, including Kolkali, Duff Muttu, wedding songs, lullabies, and war songs. Despite this diversity, there appears to be insufficient scholarly focus on its musical and rhythmic aspects. The instruments used, their rhythmic applications, and comparisons with instruments from other cultures deserve attention. The acoustic variations can indeed be recreated using electronic devices, yet we often overlook analyzing the original forms of these sounds. There is a lack of exploration into how our ancestors developed these musical traditions, which could reveal the depth and breadth of this culture’s roots. Examining the construction and history of a single instrument could provide profound insights into our current position and its evolution. This exploration could lead us towards understanding the multicultural exchanges and the rich diversity within our cultural heritage. Theyyam and Thira are ritualistic art forms from Malabar, particularly from the districts of Kannur, Kasaragod, and Kozhikode in North Kerala. Although these art forms combine dance and elaborate costumes, the “Thottam Pattu” (songs) used in Theyyam deserve serious attention from classical musicians. These songs often contain the primitive applications and original forms of the ragas that have been refined in our classical music. Studying the vocal renditions in Theyyam can reveal these early musical expressions, offering valuable insights into the origins and evolution of our musical traditions.

Numerous songs and their musical structures are prevalent in North Kerala, with Mappila Pattu breaking through religious barriers to reach a broader audience, transcending its origins within the Mappila community to become a part of the wider Malayali culture. Discussing such a vast heritage within the confines of a short article is challenging; we can only touch upon the surface of this rich tradition. We have meticulously preserved oral traditions through written works, leading to the creation of books. Over time, we have lost the unique singing styles of great artists from this field, which is indeed a significant loss. In his study of the Prakrit language, V.T. Kumaran says: “The expanse of the Prakrit language, much like the ocean, encompasses an immense collection of common people’s emotions and thoughts. Ignoring Prakrit would render any study of Indian culture incomplete.” Researchers studying folk songs from any region must understand the area’s myths, geography, historical inhabitants, labor practices, social relationships, and social conditions. It is crucial for new scholars to explore these aspects with fresh perspectives and strive to complete the research comprehensively.

Numerous songs and their musical structures are prevalent in North Kerala, with Mappila Pattu breaking through religious barriers to reach a broader audience, transcending its origins within the Mappila community to become a part of the wider Malayali culture. Discussing such a vast heritage within the confines of a short article is challenging; we can only touch upon the surface of this rich tradition. We have meticulously preserved oral traditions through written works, leading to the creation of books. Over time, we have lost the unique singing styles of great artists from this field, which is indeed a significant loss. In his study of the Prakrit language, V.T. Kumaran says: “The expanse of the Prakrit language, much like the ocean, encompasses an immense collection of common people’s emotions and thoughts. Ignoring Prakrit would render any study of Indian culture incomplete.” Researchers studying folk songs from any region must understand the area’s myths, geography, historical inhabitants, labor practices, social relationships, and social conditions. It is crucial for new scholars to explore these aspects with fresh perspectives and strive to complete the research comprehensively.